This is a case study I have been meaning to publish for some months on how a reflective activity, videotaping, and self- and peer evaluation were applied to a formative assessment in an elective module on an undergraduate/postgraduate, degree programme.

Background

After years of teaching one of my favourite modules open to undergraduate and postgraduate students, in the School of Arts and Social Sciences, it suddenly occured to me that my highly motivated students simply did not know or really understand what we assessed them on. The Assessment Criteria were there, detailed, big and clear, handed out to them, but every year, numerous students would get weak grades, not due to lack of preparation, but to lack of understanding key criteria.

One of our formative tests was an oral presentation, taking place in March every year, and which was repeated in the end-of-year final summative tests, only four weeks later.

For years I have had the privilege to observe colleagues’ teaching, and have learnt a tremendous lot, some of which I have happily incorporated into my own teaching. With every March approaching I kept wondering: ‘How can I get my students to learn from other students’ presentations, and to better see what they should improve on in their own presentations?’. Surely they simply needed to better understand what it was that made an effective presentation in front of an audience and to critically watch other students’ presentations, to learn from them. At that time I realised that I had to make sure that my students really understood the criteria, and that this should be at the back of their minds when they prepared and presented.

Assessment activity

So back in March 2010 I decided I would include a short activity in class asking students the following question: ‘What do we look for in a presentation in front of an audience?’ Students would discuss this in groups and we would gather key points together.

I anticipated little interest with this discussion, but after six months of discussing a wide variety of subjects in class (by then the group had jelled and students were comfortable discussing anything!), the group took it in their stride and the results were remarkable. There were aspects which did not come out of the reflection so I asked my group to read the Assessment Criteria for this exercise, and compare them with their own list. The whole exercise had taken thirty minutes and I was hoping it would prove fruitful.

Two weeks later students presented, and I was pleased to see that the age-old bent-down heads in notes in front of other students was no longer on the agenda. Students were making tremendous efforts to ‘talk’ to their audience, rather than hide behind their notes, which was one of the typical ways they would previously present. One major criterion was communication, and they were now scoring better on this. I asked them to email me, telling me which presentation they had liked best, and why, in a few lines. Once this was done, I posted filtered results for everyone to read before the summative tests.

We briefly talked about the experience and I jokingly said to them that I should have filmed them and allow them to see their own performance so that they may compare it to the Assesmment Criteria, and was surprised to see no head shaking in horror. One student came to me after the session, and said he would have quite liked to be filmed, actually.

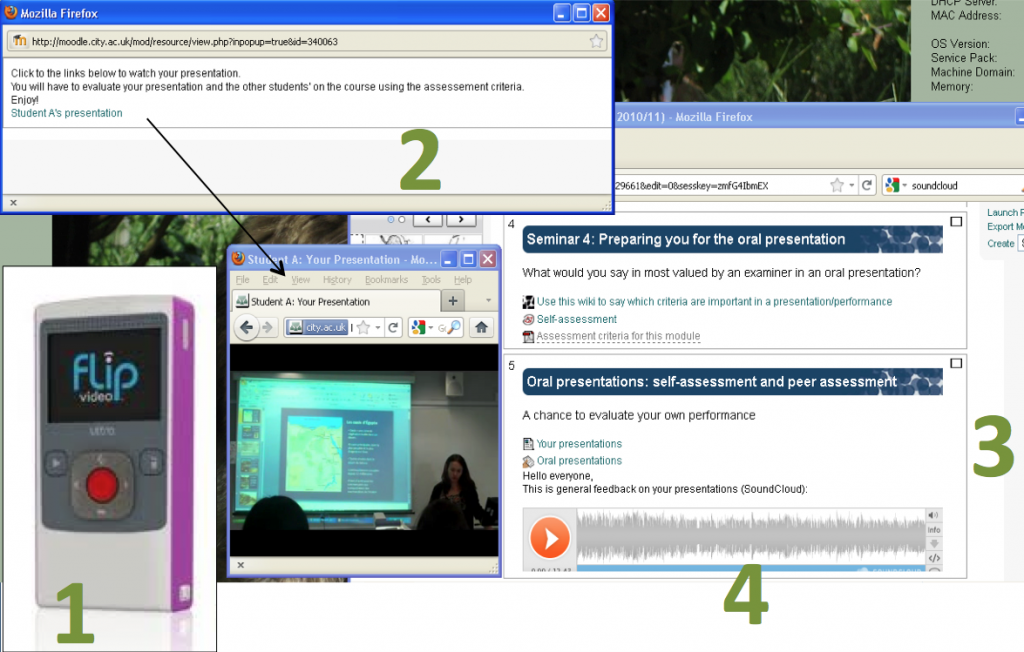

Video

A new academic year started. This year, the school was introducing flip cameras, which I had heard of. I said to myself these cameras would be a lot less intrusive or intimidating to students. I knew of simple editing tools and the possibility to stream videos centrally thanks to colleagues in the MILL. So I decided this would be an opportunity to go one step further from last year.

I decided to continue with the Assessment activity, and the informal peer evaluation, and to combine this with an informal self -evaluation based on one’s videotaped presentation, for the formative exercise only, in view to help my students better present on the day of the exam.

2010-11 coincided with the introduction of Moodle in our centre. I decided to investigate the wiki a little, and could now display the Assessment Criteria in my module’s front page.

I also decided to take the PgCert in Academic Practice course at City, and instantly knew that this mini-project would be my PPDP. I was keenly aware that the process would have to be smooth and clear to my students, and that I would need their consent to film them. I mentioned filming early on, to test their reactions but did not encounter any opposition or fears. I simply told them that this would be an exciting opportunity, and they would be able to go away with a video of themselves and that this would almost certainly be useful to add to their cv or portfolio.

At that point, but not quite for the first time, I turned to theory and published articles to help me with this trial project. I had attended several lectures on what used to be called ‘independent learning ‘ in the early 2000s, and had attended seminars led by the LDC circa 2005 on peer assessment. I had also taken part in an audio feedback project in 2009-10, which matched my deep interest in more personalised feedback to students. When I started looking for other projects that had used filming as a means to better evaluate oneself against criteria, I did not find such a study.

I did however find studies which confirmed my intuition that self- and peer- evaluations fostered critical self-assessment skills (Boud, 1995), and some where students had reported that peer assessment had made them think more, and made them work in a more structured way (Orsmond et al, 1996).

I also found that video had been used as means to “notice things which you could not at the time” (Claydon et al, 1993) and came across a gentle reminder to be cautious as it had been revealed that gender differences in self-perceptions exist in post-task self-evaluations of performance and that males tend to overestimate themselves, compared to females (Beyer, 1990). I was pleased to read that that over-inflation in self-marking could be prevented by combining peer assessment with self-assessment or co-assessment (Dochy,1999). I was ultimately aiming for developing a peer learning culture and a sense of active cooperation between teacher and students and “assessment for the longer-term” (Falchikov et al, 2007).

March was again approaching, and I decided to get myself filmed with the flip camera, both because I wanted my students to familiarise themselves with the camera with us in the classroom, and also because I thought it would be useful to self-evaluate my own teaching and go through a similar experience as my students’ in a few weeks’ time.

The results

Two weeks prior to the oral presentations, I went ahead with the Assessment activity, and got a similar enthusiasm with the exercise, to my still huge surprise as I still feared my students would find the exercise dull and dry. But no, they did want to know what makes a good presentation, or at least how to get better grades.

At that point I set up a rudimentary wiki, open for a week, where students who had not attended could join in the reflection. The wiki asked the same question which we covered in class: ‘What makes a good presentation in front of an audience, in your opinion? Write down key words, and explain how this can be achieved.’ I added an example to help start the conversation.

Again, results were similar to the previous year. Students were again asked to compare with the centre’s assessment criteria, and to synthetise these in view of their preparation.

The big day arrived. The flip camera was set up rolling and students were, again to my surprise, not really affected by the camera ‘s presence. Some appeared nervous but not more than in previous years.

I promised that they would be able to watch their own presentations by the following week and that they should, in the meantime, email me their comments and say what had been their favourite presentation today, and explain why, bearing in mind the criteria we had discussed.

I did not want to use Moodle’s forum as I wanted to screen these answers and make sure comments remained anonymous. Instead I posted a summary on my module’s page, keeping the most relevant comments.

I had booked an afternoon at the MILL to edit my videos and opted to publish these on disks so that my students would able to go away with them. (I later streamed one of them to the server.)

The next step required of my students to self-evaluate themselves, briefly and email me this. Then I would respond to this, giving them specific advice on how to tackle one or more areas for improvement they had identified themselves. I read sound, if somewhat overcritical observations. All the students who presented took part in the follow- up self- and peer evaluations. I had granted 10 % for this for this formative test. It turned out to be enough to guarantee participation.

The results of this dialogue were particularly useful for those students who were, or who felt they were the weakest in the group. One particular student had found that she simply was not fluent enough to ‘hold’ her listeners’ attention, compared to other students in the group and seeing her videotaped performance, she thought the delivery too soft. I asked if she could identify what it was that she had liked so much in Student B (which she had chosen as her favourite presentation), and if she could think of ways she could adapt what she liked to her style. She had admired Student B’s dynamism. I pointed out that Student B often used small gap-filling words which helped with a more fluid delivery, and that her voice fluctuated more and helped the listener follow the thread.

On the day of the summative test which was a similar exercise but with no audience, she performed remarkably well, with such confidence and an obvious understanding of what required of her, that her final grade was nearly as high as the student she had admired.

Conclusion

I would thoroughly recommend incorporating an assessment activity into any assessed teaching you are doing, and think of devices or tools you may use to help students evaluate their own work better. It does not have to be long. The Assessment activity took 30 minutes in class. Editing , copying on CDs and streaming took a couple of hours, but with experience, now takes me a lot less. The peer evaluation summary and self evaluation dialogue via emails probably took an hour but I was now able to minimise my feedback to shorter points as we had discussed these in more details than in past years.

The process I chose to follow above was suitable for my needs. I wanted to help my students understand our marking criteria better so that they could identify their own areas for improvement, by themselves, with only minimal guidance. Helping your students think, make decisions, be self-critical in a positive and constructive sense are all qualities that will be valuable to them later in the workplace.

This project was valuable to me too, on a personal level. Incorporating new innovative techniques has helped me keep my enthusiasm for aspects of the learning which most us find dull and begrudge, that is of Assessment.

I would recommend that you inform you students well, and keep the process as simple and clear as possible, and improve it in subsequent years. Looking back I think I should have better prepared my students in providing constructive written feedback, for instance providing examples, or using a Moodle feedback questionnaire in order to rate presentations.

Now that a lot of us are also getting more familiar with Moodle, it is possible to swap the face-to-face Assessment activity with an online wiki activity, so long as it is well integrated into your process, easy to use, with a clear timeframe and followed up by a class discussion comparing your students’ wiki list with your department Assessment Criteria list.

I think that this process helped my students develop important study skills, such as collaborating, identifying key action points and acquiring a certain degree of responsibility in one’s approach to learning.

References

Beyer, S (1990) Gender differences in the accuracy of self-evaluations of performance, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, Vol 59(5), Nov 1990, 960-970

Boud, D (1995) Enhancing Learning Through Self-Assessment. London, Kogan Page.

Claydon, T and McDowell, L (1993) Watching yourself teach and learning from it, SEDA Paper 79, 43-50.

Dochy, F, Segers, M and Sluijsmans, D (1999) The use of self-, peer and co-assessment in higher education: A Review , Studies in Higher Education, 24:3,331 — 350 (Last accessed 7 March 2012)

Falchikov, N and Boud, D (2007) Rethinking assessment in higher education: learning for the longer term (Last accessed 7 March 2012)

Orsmond, P, Merry, S and Reiling, K (1996) The importance of marking criteria in the use of peer assessment. Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education, 21 (3), 239-250.